Getting punched by a Nazi

There is no power and control in violence. PLUS: Middle schoolers being crazy, MLK Jr. demonstrating nonviolence, and a rap from Lecrae.

I always laugh when politicians, pundits, and people glued to their phones claim that teachers are indoctrinating their students. As a former teacher in both public and private schools, I WISH I had the kind of influence these figures attribute to my position.

I wish I could indoctrinate kids to wash their hands…put on deodorant…pick up their trash…so many basic things.

However, there was one behavior I did try to indoctrinate the kids with—I’ll fully admit it. During my time teaching, especially in an inner-city Title 1 public school, I tried my best to influence students toward a quite radical position: violence is bad.

You see, I taught middle schoolers—not exactly known for wise decision-making. Hormones bounce around their undeveloped brains. They discover that the opposite sex is kinda cute. They jockey for popularity and prestige, all while their bodies start changing in weird and terrifying ways. It’s a tough time!

Many of these kids were either raised in a “violence” culture or absorbed it from friends or media. Coupled with their developing sense of self and values, they often adopted the belief that retaliation was necessary and that force was the only way to get what they wanted.

I probably broke up five fights myself in one year teaching sixth grade at a public school. On one occasion, I held back a rather large kid with my forearm as he swung punches at another student who had hurt his feelings. Another time, a girl started hitting another girl’s head nonstop, and I had to swoop in and separate them.

But violence doesn’t only appear as physical. Words can be weapons, too. Many students believed the person who had the last word "wins." This meant arguments spiraled into never-ending streams of “yo mama” jokes and some of the lamest insults I’ve ever heard. Honestly, the insults were so bad sometimes I wanted to laugh—but I was supposed to be mad at them. In both public and private Christian schools, I also witnessed ugly racism, where students used slurs and judged one another by skin tone and ethnic background.

On multiple occasions, students told me that their parents had explicitly instructed them: “If someone hits you, you hit them back.” I had the uncomfortable duty of explaining that’s not how we do things at school, even if your mom or dad says it’s okay.

But worse, was a situation at my school not with one of my students, where a mom told her son to beat another boy with a crowbar because the other boy’s mom insulted her. And he did. Likely ruined his life for that. All because his momma had a petty spat with another woman. That’s violence culture.

Against all this prevalent violence, I tried to “indoctrinate” them with a simple belief—one I draw from my faith in Jesus but which many claim to ascribe to: violence is bad.

And, what do you know, they didn’t believe me!

I told my angriest students again and again that true power comes from not retaliating. I explained that controlling oneself demonstrates superiority. It’s the weak ones who give in to their first thoughts. It’s the weak ones who NEED to punch the person who insults them. There’s nothing weaker than being ruled by impulse because it shows you lack mastery over yourself.

More than anything, I tried to model this behavior. Those kids could be brutal to me! They dug up embarrassing pictures from the past from my social media and had colorful words for me when I asked them to follow Basic School Behavior 101—like sitting in their seats. They repeatedly stole from my classroom and, on one occasion, took my favorite water bottle (covered with stickers from my world travels) and threw it in the trash. Even after washing it, it took months for the smell of pencil shavings to completely go away.

I’m proud to say that most of the time, I responded rationally. I controlled my emotions instead of letting them control me. Of course, I still enforced consequences—but I never punched a kid! Which, I suppose, is a pretty low bar. At worst, I returned some snark with snark of my own.

Nevertheless, it was tough for my middle schoolers to grasp this important life lesson. And while I grant that these youngsters had some excuses, this same culture of violence persists among adults too. (who do not have the same excuses for being dumb). Many of us feel justified because at least we haven’t murdered anyone, but we still retaliate, seek revenge, and demand restitution whenever we feel wronged.

Not The Way of Jesus

While some view Jesus as relaxing the harsher Law of Moses, he actually made his new law STRICTER in a few areas, chiefly, in the realm of murder.

“You have heard that it was said to the people long ago, ‘You shall not murder, and anyone who murders will be subject to judgment.’ But I tell you that anyone who is angry with a brother or sister will be subject to judgment. Again, anyone who says to a brother or sister, ‘Raca,’ is answerable to the court. And anyone who says, ‘You fool!’ will be in danger of the fire of hell.”

—Matthew 5:21-22

Here, Jesus equates anger (likely referring to acting out in anger or harboring persistent hostility) with murder, making both equally subject to judgment. Additionally, he says, even a mild insult is enough to condemn someone to hell!

A few verses earlier, Jesus is super explicit:

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.”

—Matthew 5:9

We are peacemakers, no war wagers. Jesus’ ethic is centered on peacemaking. To be formed by Christ means to cultivate the fruits of the Spirit, including self-control, gentleness, patience, and kindness. Christians more than anyone should know the sacredness of all life—all of us image God. Violence, then, is antithetical to the peacemaking way of Jesus.

While most Christians—and mostly anyone—would agree with the statement “violence is bad,” there’s often a temptation to add a “but” or “unless,” some kind of exception clause that makes violence acceptable. I fear this desire to create exceptions comes from a place far removed from the fruits of the Spirit. Such a desire, I believe, stems from the fruits of darkness. It reveals some attachment to idols of Safety or Power or Control.

I don’t have time to present the entire case for Christian nonviolence, but I highly recommend these works: Nonviolence: The Revolutionary Way of Jesus by Preston Sprinkle, Jesus the Pacifist: A Concise Guide to His Radical Nonviolence by Matthew Curtis Fleischer, Fight Like Jesus: How Jesus Waged Peace Throughout Holy Week by Jason Porterfield, and, of course, the four Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

What I do want to emphasize is that for the first 300 years of Christian history—before it became tied to political power—violence was almost universally seen as antithetical to the way of Christ (Bullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian History by John Dickson offers excellent insight on this topic). And we need to get back to that position today!

Violence is how the world wins. It’s the world’s default method. But as I told my students, true power lies in rejecting violence.

And there’s no better example than the life of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Punched by a Nazi

MLK Jr. may have a national holiday now, but he was hardly a popular figure in his own time—and that’s putting it mildly.

On the morning of September 28, 1962, King was on stage in Birmingham after being re-elected to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). While King was known for great speeches, this particular one was just a financial report for the organization—nothing dramatic.

But one audience member, Roy James, a member of the American Nazi Party, was furious. King had mentioned that Black entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. would perform at a benefit event in New York City to raise funds for the SCLC. James, who opposed interracial marriage, was incensed. Though he claimed to be “okay” with Black people, Davis’s marriage to a white woman crossed a line for him. He wanted races separate in all areas of society.

At 6 foot 2 and 200 pounds, an imposing James jumped from his seat, ran to the podium, and punched King square in the jaw, then again in the neck. Then another person on stage intervened, and James backed down.

King, however, reportedly stood with his hands at his sides, showing no sign of fear after the first punch. He didn’t even defend himself from the second one. As others tried to escort James away, King stopped them, insisting they pray for him instead. King declined police intervention, wanting instead to speak with James himself.

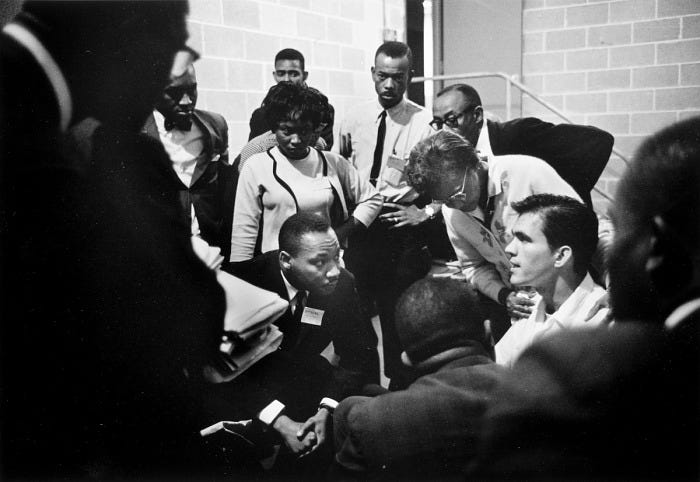

King calmly and candidly asked James why he hit him and even bought him a soft drink. That scene is recorded in the image below.

King declined to press charges (though James would later be arrested despite King’s protest). He went back up on the stage to continue speaking, inviting James to keep listening if he wanted.

King reportedly said to the crowd: “I am proud of what has happened here today because it indicates to me that the message of nonviolent discipline has been learned. That man could not have done what he did in any other similar situation without having been literally killed.”

King continued: “The system we live under creates people like this. We are working for the day when never again will a person become twisted as this man is.”

Violence, King believed, didn’t have to be the default. That day, he and his companions demonstrated an alternative: instead of retaliation, they prayed. Instead of prosecution, they sought understanding.

Violence does not have to be the default. The Christian community is a countercultural movement pushing back against that. The way of nonviolence, the way we have inherited from Jesus, is the remedy for this broken world.

And the way of peace, as Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King exemplified, is the more powerful position.

There was one notable figure in the audience that day: Rosa Parks. She later reflected on that moment as an event that cemented her belief in the movement, though at the time she already had famously refused to give up her seat on the bus.

Parks recalls: “I was so proud of Dr. King. His restraint was more powerful than a hundred fists.”

The Model

Violence is an idol many worship—including some Christians. It’s easier. It aligns with instinct. It makes us fit in. It creates an illusion of control.

The Christian rapper Lecrae notes these factors and others have consumed little boys toward violence, but that they are getting it all wrong about the meaning of strength. In the song Violence, he poignantly sings:

“Too scared of being broke to think about being betta’

Plus, we get bombarded by all these images of bravado

You ain’t really a man if you don’t follow these models

But the weakest ones follow, the strong reconsider

You can forgive much if you understand you forgiven.”

Violence is weak. It reveals a lack of control. It doesn’t foster virtue. Its fruits are dead and rotten. It’s letting the Devil dictate your actions and rejecting Jesus’ teachings, which consistently tell us: DO NOT act on the impulses of the flesh.

Jesus offers a better way.

The way of the Peacemaker is strong. It takes courage, resolve, determination, and the Spirit of Christ to respond as Martin Luther King Jr. did. Its fruits are bountiful.

If we had more MLKs and fewer reactive middle schoolers, the world would be stronger and better. As Christians, nonviolence is our radical calling. It reflects a world we all long for—a world we can only achieve by embodying this way of peace.

Stanley Hauerwas, in A Community of Character, puts it well:

“The nonviolence of the church derives from the character of the story of God that makes us what we are—namely a community capable of witnessing to others the kind of life made possible when trust rather than fear rules our relation with one another.”

Nonviolence doesn’t always change everyone—but it changes us. It frees us from worshiping the idol of violence and empowers us to control our responses. It’s the right way forward.

So, with all that being said, there’s only one real question left: if you get punched by a Nazi, what will you do?

Latest Podcast Episode

Is Deconstruction Divine? - Scot McKnight

Dr. Scot McKnight, New Testament scholar, is on Theology Meets World with host Jake Doberenz to discuss Christian deconstruction and reconstruction of faith based on his new book Invisible Jesus. Scot shares his personal story of moving from fundamentalism to a Jesus-centered faith, discussing the meaning of deconstruction and its connection to the work…

Life Updates

Subscribe to the Theology Meet World podcast on your favorite podcast platform.

Nonviolence is sexy,

Jake Doberenz

Thanks for reading Smashing Idols. Please share this publication with others!